LULAZO #9

LULO vs the C-Market

The global coffee trade is complicated…

…And I’m far from understanding it fully.

That’s partly why it’s taken me so long to write this, but now I’ve come to know that my inexperience with the global coffee trade is the reason that I should.

In a conversation often dominated by large-scale statistics and systemic issues, it can be easy to overlook the impact of one’s own perspectives and actions and the direct type of connection they inherently have on other individuals.

So I’ll be focusing almost entirely on my company’s experience and interaction with such matters. Because it does matter.

The content here covers a lot of ground, so let’s start with some basics.

The Basics

The C-Market

Coffee is commonly traded on the international stock exchange, known as the C market price.

This price fluctuates daily. It’s based largely on harvest conditions in Brazil, which doesn’t make it representative of the highly localized costs associated with coffee production across the globe, such as labour, transportation, agricultural inputs etc.

In recent years, this price has been as low as $1.00usd/lb and the current surge comes as a shock to most coffee traders around the globe.

It also has not been updated to reflect inflation since the ‘80s.

Knowing only the statements above, it’s easy to see that this isn’t working for most producers. In fact, it’s so bad that most are consistently inches away from financial crisis.

You must be thinking that this surely isn’t the only way coffee is traded. And, while it actually mostly is, there are a few other pathways a coffee might find itself in.

Fairtrade / Organic

Fairtrade and Organic add a small premium onto the C-market. But given the fact that the C-market price doesn’t reflect an actual, viable baseline price, these small increases really don’t mean much. Organic certification can have some environmental benefits, and surely one can find positive use cases, but it’s paid for out of pocket by the producer themselves, quickly balancing out the environmental positive with financial negative (for those who are already often precarious situations).

Both are what I would call a band-aid on a bullet wound. Simply not enough to address the economic gap imposed on smallholder producers, however well-intended.

The Specialty Difference

The premium that specialty pays is often much more than the other three. It’s still often presented as a percentage increase from the C-market, which, much like the Fairtrade premium, can distort its relative impact.

It’s also accompanied by much more rigid demands on quality levels, requiring more effort and investment, which complicates things further. It’s also worth mentioning that the deciding factor of this premium is usually based on the perceived quality of the coffee, which is, more often than not, determined by the buyer.

Samples are sent to the roaster or importer for approval at multiple stages of a coffee’s journey in its country of production. Each time (which varies depending on the supply chain) is an opportunity for the buyer to claim an issue; be it taste/cup score, number of defects, etc.

Unfortunately, the habit of buyers (importers, roasters) breaking a contract or even dropping a partnership over minute changes in cup quality is all too commonplace.

Such things are bound to happen when the dynamics are heavily skewed in favour of the buyer, and the sole priority is highly nuanced differences in perceived quality.

All of a sudden, when taking into account the added effort and risk, those premiums on the almost-randomly generated C-market price don’t seem so high, do they?

For all its drawbacks, the C-market is something that people can rely on to buy their product, day in, day out.

Specialty coffee, on the other hand, represents the opportunity for greater gains which come with greater risk, effort and investment.

FOB / FARMGATE

I’d like to make a quick distinction here between these two connected, albeit, distinct pricing systems before we go any further.

The pricing terms mentioned above (the C-market and it’s derivative pricing structures: Fairtrade, Organic, and Specialty) are all expressed as FOB or Free On Board. This means the price reflects all costs involved in coffee production, preparation for export and logistics to its port of exit. This different from the price given to the producer, which is referred to as farmgate.

Pricing expressed in FOB terms makes it difficult to know the farmgate price, as the number of hands the coffee goes through differs in each supply chain. This makes it harder to assess the actual impact of the price paid for a coffee, which is often glossed over in marketing campaigns and branding efforts.

A Note on Dry-Milling

One final note before we continue. Dry-milling is the part of the coffee’s journey that comes after it’s finished drying at the farm. It’s the removal of the outer layer of skin, commonly called parchment.

While there are some examples of hulling machines on farms, it’s an intensive process that requires heavy machinery if it’s to be done in an efficient manner. Entire sites, known as dry mills, are dedicated to this process.

The volume of coffees going through a popular dry mill are staggering. The logistics can be challenging and this is where the work of solid exporters or importers is crucial. Organizing logistics from the farm, to a busy dry mill, to a busy port while maintaining quality and traceability standards is a daunting task and there is a clear need for experience and attention in achieving it.

Yet dry-milling is an undeniable inflection point in the supply chain. It’s often the stage of the journey from farmgate to FOB where a lot of value is added to the product and captured by whoever handles the process. On the quest toward a more impactful supply chain, it seemed worth looking at.

A Pathway Forward?

As I said at the beginning, the sheer size of this problem can be overwhelming. My “background” in backpacking led me to value direct, authentic connection above almost everything else.

So that’s what I sought, trusting that the rest would fall into place after.

Most coffee professionals spend years in their consuming country forming their perception of the industry before travelling to “origin” on a buying trip. Their opinion of a coffee has a lot to do with how much it costs. With little understanding of the general effort involved in producing the coffee, and even less about the people they buy it from, it’s easy to see how this perpetuates a disconnect. It’s much harder to create change once habits are formed.

By beginning my learning journey in producing countries, I hoped to bridge this disconnect as best I could.

ENTER THE LULO

The Mission

LULO, in its own tiny way, seeks to reshape the coffee trade.

Since the company’s inception four years ago, the mission has been to cut through the barriers of scale and grow a comprehensive, direct trade model as slowly as necessary for that to be as literal as possible.

Early on, I decided this would be best achieved by working with only a few farms, at least in the beginning.

Working with just five farms in two countries allows for a number of benefits:

Allows more frequent and meaningful contact

Builds trust and accountability

Reach significant volumes faster

Makes independent logistics feasible

Enables more collaboration

Creates conditions for awesome coffee

This style of sourcing has allowed everyone (producers and roaster alike) to become calibrated both economically as well as sensorially.

We all cup together and learn about each others’ palates and preferences. We come to understandings on what type of varieties and processes work for each farm and why. I also get a sense of the costs and risks involved in production.

In turn, I can convey the realities of the consumer market I find myself in, and we can build accordingly.

When it comes time to make the trade, no samples or contracts are necessary. We plan quantities and logistics months in advance. The trust we’ve built allows us to act in good faith and mutual understanding.

We believe that it’s this type of trust that’s needed to push the specialty industry forward.

Pillar + Peak Pricing

When it comes to pricing, we follow a producer-created framework that brings the consistency of the C-market and value-add of specialty, and then some.

We sought a value distribution that was more favorable to the producers involved. To achieve this, we decided to trade in export-ready green at the farm level, instead of parchment. This means each producer is responsible for their own dry-milling. Despite the logistical challenges and risks of the process, the producers and I thought it was worth exploring and in doing so, we have essentially merged farmgate with FOB prices.

Pricing is divided into two (familiar) categories: Pillars and Peaks.

Pillar pricing is for the coffees that make up the bulk of each farm’s harvest and therefore the bulk of LULO’s purchases, sitting at about 80% of the yearly volume. The pillar coffee price is set at $4.50usd/lb, regardless of precise cup score. Consistency is the primary goal here.

At $4.50usd/lb minimum farmgate price, we all feel confident that this is firm ground to stand on.

Peak pricing is where we let the variables come into effect. Taste, additional required resources, lower yields, riskier processing are taken into consideration as prices are agreed upon. They land within a range between $5.50usd/lb to $18usd/lb, with the average for 2024 being $7.70usd/lb.

Trust the Process

By implementing these two farmgate-level pricing categories, the producers and I have managed to go from airfreight shipments of 60kg at a time to now shipping containers with multiple tonnes without changing the pricing structure.

I can’t say it’s been easy. In fact, at the beginning I was paying too much for shipping (without lowering farmgate/fob prices to compensate) that it’s safe to say I hardly made it out alive.

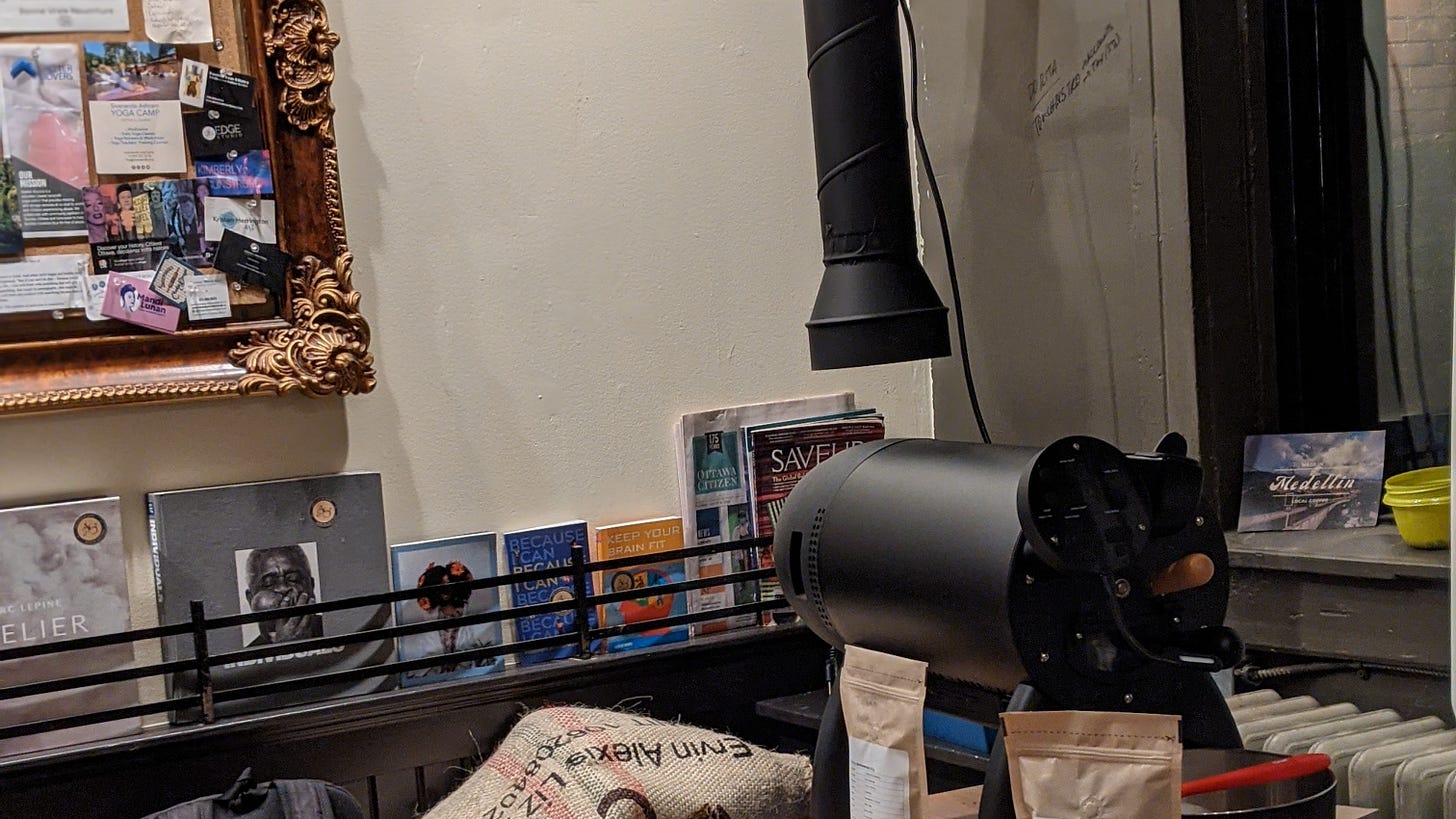

12+ hour roasting sessions with one, then three 1kg electric roasters. Shipping every coffee via DHL. Wildly expensive and time-consuming. I was barely able to keep up.

But the original mission kept me going. Over the last four years, through an untold number of learning curves, the greatest lesson has been that it’s all worth it.

Now, LULO is running more efficiently than ever, with a new roaster and tolerable ocean freight rates. It’s starting to look like this is actually working. This has all been achieved without bringing on investors or crowdfunding. Not even an influencer.

Just a heck of a lot of support from people who are down with the LULO vision.

Shared Story = Shared Risk = Shared Accountability

By approaching the industry this way, I hope to address what is at the crux of a lot of prevalent industry issues, that is - a lack of accountability.

By working with so few farms so consistently, the LULO brand is so synonymous with coffees like the Nasa Community Blend, Finca Alcatraz Caturra or the Don Eli Typica that it just wouldn’t work without them. LULO’s wholesale and home customers alike now have clear expectations, whether quality or sourcing based.

Any significant changes to the menu would make me responsible to them as well as the producers with whom I work so closely. If I’m cancelling a contract or offering a lower price, it’s not a removed sense. Not via an importer or exporter, but directly, face-to-face.

LULO buys significant volumes from everyone it works with. It’s success is their success and vice versa. We all are incentivized to keep working together, creating beautiful experiences and beautiful coffees along the way.

By staking our growth on one another, LULO takes on more risk than in the traditional specialty “relationship” model. I become personally responsible for containers of coffee at a time, while the producers involved put a lot of faith in one person to steadily buy lots of coffee and represent them well in outside markets. It goes against the grain of the status quo in almost every way imaginable.

Through this shared risk and shared experience, we become accountable to one another.

So far the results have been tangible. With our prices set well beyond C-market, Faitrade and Specialty norms, the extra risk is well worth it.

Some Thoughts

While it’s true that, to me, the LULO business model makes most other specialty roastery models seem indistinguishable from one another, I don’t share all of this to condemn importers or shame roasters. Not at all. I completely understand the difficulties of international logistics, relationship building while running a roastery, the practically margin-less endeavor of running a coffee shop, and the plethora of reasons not to do things the way I’m doing them.

I see the multitude of positive changes happening congruently in the industry.

I don’t believe the industry benefits when we start calling each other out for differences of opinion or practice, when we probably all have something to learn from each other. I believe that good faith understanding between all roles in the industry is crucial to moving forward.

In sharing this, the hope is to inspire roasters to think outside the box and not discount their individual impact and capacity for change. I also hope it serves as a nudge to roasters to put their ideas into action, however radical they may seem or slowly they are implemented. It’s almost 2025 and if you’re talking the talk, you best be walking the walk.

But most of all, I hope this inspires budding coffee people to begin (or really dive into) their learning journey in a producing country.

The reversal of the coffee learning pathway is probably the most radical way to bring about change in the industry.

Acknowledging that the finest, most detailed and intimate coffee education can be found in producing countries is an acknowledgement that these people and places have a lot more to offer than just a cash crop. The pathway toward a more equal industry begins there in every sense.

The root of equality begins before prices are being set; it begins with shared understanding.

The earlier you can begin learning from someone who produces coffee, the more mutual your understanding will be, the more your perspective and eventual actions will advocate for them - no matter what journey you end up taking.

So as I said in the beginning. I am far from fully understanding the C-market and the coffee crisis as a whole. But by choosing to take responsibility for my role in the industry and literally show up for those I work with, I wholeheartedly believe that LULO is already making an impact. An impact that is bound to grow along with the people involved.

Remember, despite how hopeless everything can seem, there are lots of reasons to get stoked. Find that stoke and let it be an agent for positive change, however that looks for you.

- Much Love,

KEV

I’m a small producer hoping to do everything in house with direct sales to North America. Wish me luck! Great article. I think people understanding what a bean goes through is a great start to educating people…..coffee should cost more! 🙏🧑🌾

Such an interesting post! Thanks for sharing. Your story is very inspiring, it really does feel overwhelming sometimes as to where to start to contribute positively to the coffee crisis. And I had no idea about the separate dry milling of parchment green beans, I assumed it was always done on the processing plant/farm before export so thank you for enlightening me! May I ask, are the pricing and peaks categories something you (Lulazo) have decided to implement, or is this more widely done by other direct coffee traders? And do you have any suggestions as to how we can help producers increase their value of their green beans if they cannot currently afford dry milling machinery? Would be great to hear more!